- 2023

- Unrated

- Janus Films

- 2 h 23 m

- 2023

- Unrated

- Janus Films

- 2 h 23 m

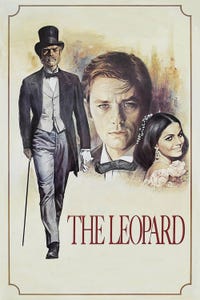

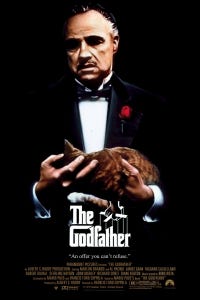

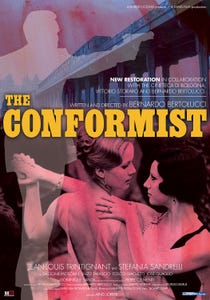

Summary In the late nineteenth century, Danish priest Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove) makes the perilous trek to Iceland’s southeastern coast with the intention of establishing a church. There, the arrogant man of God finds his resolve tested as he confronts the harsh terrain, temptations of the flesh, and the reality of being an intruder in an unf...

Directed By: Hlynur Pálmason

Written By: Hlynur Pálmason

- 2023

- Unrated

- Janus Films

- 2 h 23 m

- 2023

- Unrated

- Janus Films

- 2 h 23 m

Godland

Where to Watch

Summary In the late nineteenth century, Danish priest Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove) makes the perilous trek to Iceland’s southeastern coast with the intention of establishing a church. There, the arrogant man of God finds his resolve tested as he confronts the harsh terrain, temptations of the flesh, and the reality of being an intruder in an unf...

Directed By: Hlynur Pálmason

Written By: Hlynur Pálmason

Where to Watch

Top Cast

20 Reviews

1 Review

0 Reviews

20 Reviews

1 Review

0 Reviews

18 Ratings

6 Ratings

3 Ratings

18 Ratings

6 Ratings

3 Ratings