'Kaleidoscope' Creator Unpacks the 'Watch in Any Order' Structure to His Heist Drama

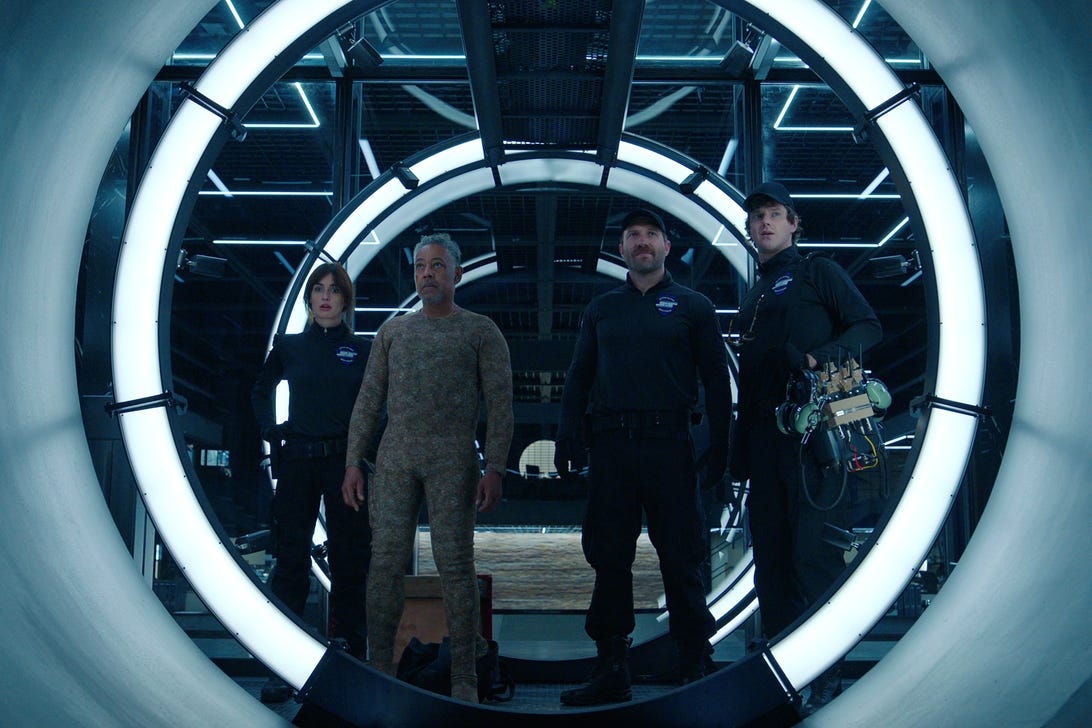

The cast of 'Kaleidoscope'

NetflixWarning: This story contains spoilers for Kaleidoscope, streaming now on Netflix. Read at your own risk!

Eric Garcia isn't alone in loving a good heist.

"There's such an interesting thing, where we loathe criminals — especially in America, we're fans of locking a lot of people up — but for some reason, we find heisters fascinating," says the creator of the new crime drama Kaleidoscope on Netflix. "I think that's because they, to some degree, use their minds to get around [the problem]. It's not that they're taking a gun and robbing a place — although there is a fair amount of that in the show — but at the end of the day this is a game of wits. These are the gentlemen thieves."

In Kaleidoscope, the gentleman at the center is mastermind Leo Pap (played by Breaking Bad's Giancarlo Esposito) who is seeking to rob security titan Roger Salas (Rufus Sewell), with the help of weapons specialist Ava (Paz Vega), explosives expert Judy (Rosalyn Elbay), safe cracker Bob (Jai Courtney), smuggler Stan (Peter Mark Kendall), and driver RJ (Jordan Mendoza). While there is a treasure trove of money at the end of this rainbow, this is of course not the motive for Pap.

"It's never about the money," says Garcia. "They're about the thing you can't get your mind off of and you can't stop yourself from doing."

What Pap is really after is something the viewer comes to discover in a unique manner for serialized television. The limited series is designed to be watched in the random order of the viewer's choosing. One episode is set six weeks before the heist, another one sets up the relationship between Pap and Salas, seven years prior. After viewing all the colors of the kaleidoscope, the show culminates in the episode "White," where the heist itself serves as the finale for every viewer.

Here, Garcia talks to Metacritic about the structure of Kaleidoscope, the challenges of breaking the rules, and hiring the right people for a heist.

Why make a show that you can watch in any order?

Well, why not? Some of it was just a challenge. Some of it was, if there is a way to do this, I think it could be really fascinating if paired with the right story. This is all about different facets of character and different ways to see things — the idea being that your point of view on these characters or the story is going to be different depending on where you come in. The example I kept giving when I was first describing Kaleidoscope was, you see an episode where I shoot my friend Brett in cold daylight and you're like, "Oh my gosh, Eric is a monster." That's because you haven't seen the episode that chronologically came before where you find out that Brett slaughtered my entire family. Had you seen that one first, you would've been like, "Aha, perfect revenge." But that means you have now seen the show differently and felt differently about the show than somebody else who saw it in a different way.

It felt like a heist was an interesting way to go because they're usually about loyalties and hidden identities and subterfuge. You might see one episode and have a certain amount of information and then you see another one and that's information, not just that you didn't have but you didn't know you were supposed to have. To me, the excitement comes when you start talking to other people about it, when you start comparing notes, when you watch it a second time in a different order and you get different things from that order, plus the knowledge you had from the first time. I just thought that was exciting. But the short answer is, because it seemed fun.

I assume that there are practical challenges that come up as you do something like this. What did you discover in the process?

There were multi-steps of practical challenges. First, of course, was in the writing. When we got the green light, I got together an amazing writers' room of smart, weird people and we got to it. One of the things we quickly found is that you have to abandon certain rules that you're used to. You have to abandon set up and call back and punchline — or you have to just look at them in a different way. A resolution is not necessarily a resolution if somebody hasn't seen it. So, it can act as resolution, but it almost also has to act as a jumping off point for something else. Similarly, the way we conventionally think about an eight-episode season, there's ways you structure that season and tell that story. We had to abandon that. Now by the same token, these characters live in linear time and they have to react normally and be who they are. So, you're trying to do that at the same time as you're trying to get it up on its feet.

Then, once we had the show in script form, it was important that everybody on the show had a sense of what we were doing. There are a million Easter eggs in the show. Some of them are just fun, some of them are actually important to understand the characters or the plots. So, everybody needed to know everything, and that included our directors. We had four directors doing two episodes each. Most TV directors, they come in, they do an episode or two and they leave. They don't need to know a ton, other than the information they have. But our directors, they needed to know everything because a lot of things connect to other things. We have shots that are meant to approximate other shots in other directors' episodes that may not have been shot yet. So, I needed to hook these directors up with one another and say, "OK, when you're doing this scene, what's your framing on this scene? You may not be shooting this other scene for three months, but we need to discuss the framing now."

So, you can watch everything in a random order, but "White" is the last episode for everybody?

Yes, the first seven are all a jumble and then "White" is the combination of all the colors and, when you look at light and color theory, comes last. The idea for "White" is that it acts as a skeleton key. We talk about certain scenes in the show as being tri-part scenes. Each episode has one scene, essentially, where you watch it the first time and you go, "OK, I get what that scene's about because I'm watching television and I know stories." Then, once you've watched all the colored episodes, theoretically that scene would now mean something different to you because you understand people's motivations. Then you watch "White," and it unlocks a third part to it. If you were to watch "White" first, because it's not designed this way, it's the only one where you'd know what's going on but you would not have any of the satisfaction that watching it last would have.

Considering that the whole creative exercise is to jumble this up, why was it important to have the skeleton key at the end?

I'm not a rule follower and I'm not a rule breaker. I broke all these rules and there was still some part of me, especially when it comes to this genre, that wanted finality in a show which is not really about finality but about redoing the same things over and over. There are characters who find a way to break out of their cycle and I felt like you needed that. We needed that as filmmakers, we needed that as an audience. At one point, it was full on, "Anything could end up last," and it didn't feel as fulfilling. We never shot it. The scripts didn't even get written that way. By the time we were writing, we had already decided there would be this last canonical episode.

I feel like for something like this, there's more of an emphasis on getting the right actors. How easy or difficult was it to find this cast?

It was a combo of easy and difficult. Leo, we knew had to be this deep, complex guy who both A.) is a criminal and B.) brings people into this thing for his own reasons that he is not necessarily divulging to them, which means he's not necessarily thinking of their wellbeing, but he is also in many ways a good person that has this inability to get out of his own obsession. So, we knew we needed somebody who could play all these sides. Julie Schubert, our casting director, brought up Giancarlo, and I was like, "Well, he's not available, he's doing [Better Call] Saul." And she said, "No, he's got a break right now. He could do this." They sent him the script and he responded very quickly. He said he understood this character. He's so nice. He's such a good guy and earnest. I actually don't have many bad Hollywood stories, but he is one of the most earnest, thoughtful people, let alone actors, that I've ever met. I adore him. So that was an easy one.

Rufus was similarly easy. I don't know if you ever watched The Man in the High Castle, but he managed to, I don't want to say humanize the modern Nazi, because he wasn't humanizing them, but you wanted to watch him and not just because he was evil, there was something about him. I think Rufus has a darkness in him and, as a result, Rufus often gets tapped to play "bad" guys. But one thing that was important for Roger was that, if you're watching certain episodes, you understand this guy's a family guy. He actually cares. He has his reasons. And when you go back into the origin story, you can start to understand who he is and why he is.

Then you get to some roles where it took a while. For Bob, we were looking at all these Americans and they were great, but they were playing charming assholes. I was just like, "I think I need an Aussie." I say that being friends with a lot of Aussies. Jai is also ridiculously nice, but he hides it well. I don't know if you've seen the show yet, but in "Pink," Bob's episode, I absolutely adore what he did.

Because this is not a "hit your mark and park" kind of show, I suppose you've got to get people who are really invested.

One hundred percent. A perfect example: Rose started buying chemistry textbooks immediately. She started a Judy Journal. Peter sent me this 75-page thing from Stan, which was a tone poem, but it was Stan's life up to that point. They just got into it. How they can dive into these characters and really become them is still a bit of a mystery to me. But everybody needed to get into it and really throw down, and they did. Oh my God, Paz, she's just the best and so excited every moment of this thing. She would come up and be like, "I can't believe we get to be here." And I'm like, "Paz, you've been doing this for 30 years." She's like, "This is just so exciting." She's so fun. Obviously in our show she's playing a bent lawyer, who you also find out has her own reasons for being a thief, and I think she pulls it off really well.

All things considered, do you have deep regrets about the structure now?

[Laughs] I have no regrets. You know why? Because it's madness. Look, making any television show or movie or anything, they are insane propositions. You walk on set and there's 300 people there, shooting for 12 hours to have two minutes of footage, which eventually we're going to have to go into a room and stare at and move around and cut out a minute of it so we can have the 58 seconds that we really need. It's insane. That said, if you're going to do it, you may as well try to do something that hasn't been done. So, for me, no regrets right now. If you would've asked me the last day of principal photography when I can only imagine the dead-eye stare in my eyes and whatever toll it took on my health, maybe I would've had regrets then, but looking at it now from six months later, I'm good.

Get to know Eric Garcia:

The novelist wrote the book Matchstick Men, which was made into a movie with a Metascore of 61 by Ridley Scott, before venturing into screenwriting with Repo Men (32), based on his own novel, and Strange But True (55). He moved into producing with The Autopsy of Jane Doe (65), Cassandra French's Finishing School, and the significantly less sinister teen sitcom Alexa & Katie.